Kubernetes Admission Controllers: A Dive Into Policy Enforcement

admission controllers webhooksKubernetes has revolutionized how we deploy and manage our applications. Ensuring compliance, security, and operational best practices across a cluster requires robust guardrails. That is where we have Kubernetes Admission Controllers—the gatekeepers of the cluster. Here, we will explore how they work, why we need them, and how we can build some custom policies tailored to our organization’s needs.

Introduction (From A Layman’s POV)

Imagine you are the security guard at Area 51 (a restricted area - I wouldn’t happen to know anything about that). You get to make the decision on who enters or not based on some factors you are looking out for. You want to make sure that:

- only authorized people can enter.

- people entering follow certain rules, like having an ID badge.

- visitors who have been granted access need some modification to their status, like assigning them a guest/visitor badge.

That is what Admission Controllers are. They are these security guards that stop and check requests coming into the cluster, before these requests are permanently turned into objects, ensuring that only authorized, valid and compliant requests go through.

What are Admission Controllers?

Now that you have been primed on what Admission Controllers are, and before we dive into what they are, let us look at the way a request for creating or modifying an object flows through a cluster before an object is created or modified.

Kubernetes has an API Server which acts as the central location for all requests coming into the cluster. If you are thinking that the API server resides in the control plane of a Kubernetes cluster—you are right!

The API Server exposes itself via an HTTP REST endpoint where users/clients connect to and send their requests. These requests go through the following main stages: authentication ==> authorization ==> admission.

Read all about the API Server and the request flow here.

Before we get to what admission controllers actually are, let us refresh our memories of what controllers are in Kubernetes. A Controller is a control loop that observes the state of a cluster, compares it with the desired state, and takes action to reconcile the actual state with the desired state.

What an Admission Controller does to intercept API requests made to the API server, makes sure the requests pass a certain criterion before being persisted in the etcd datastore.

Tying that into the Controller definition, the Admission Controller listens for requests being made to the API server, intercepts these requests, checks if they match with the desired state of the cluster, and then take some action depending on their findings.

How Admission Controllers Work

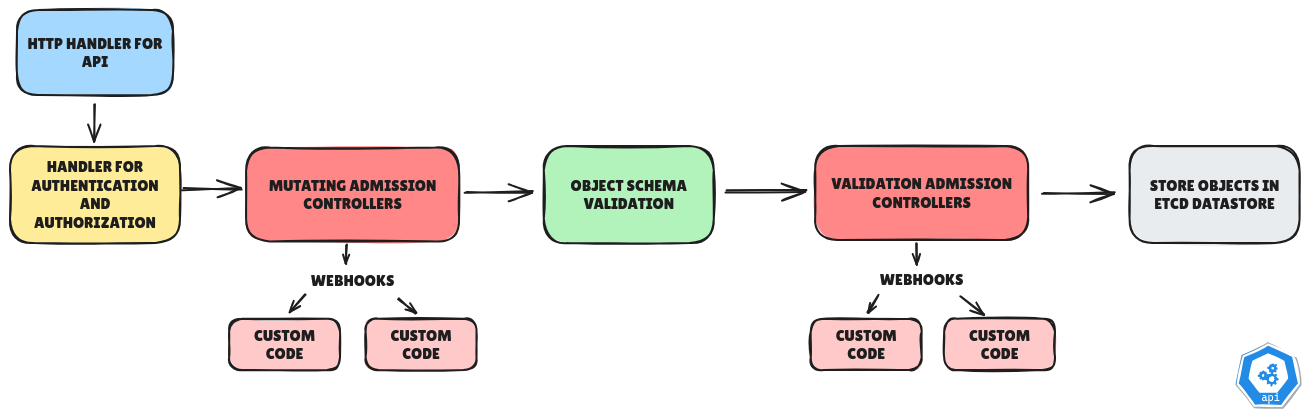

The illustration below shows the request flow to the Kubernetes API server when we have Admission Controllers in the mix.

From the illustration above, we can enumerate the stages through which requests to the API server flow.

- the API Server receives an API call via its HTTP REST interface.

- the request is authenticated and authorized.

- the request payload is run through the Mutating Admission Controllers.

- the resultant object schema is checked to see if it abides by Kubernetes object schema standards.

- the object schema is then run through the Validation Admission Controllers.

- finally, the objects are stored in the etcd cluster.

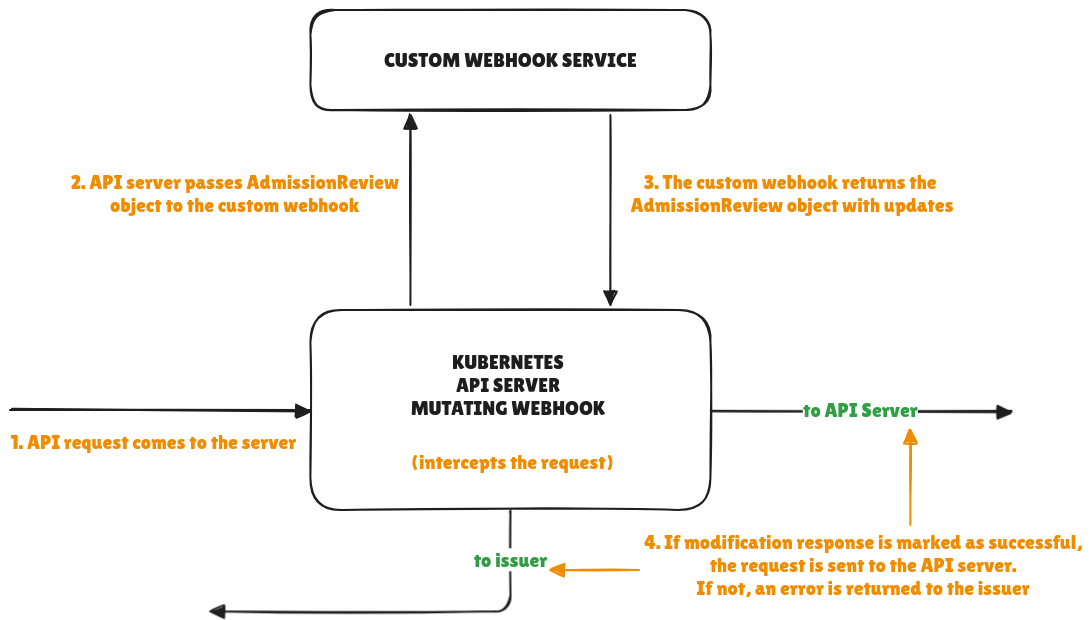

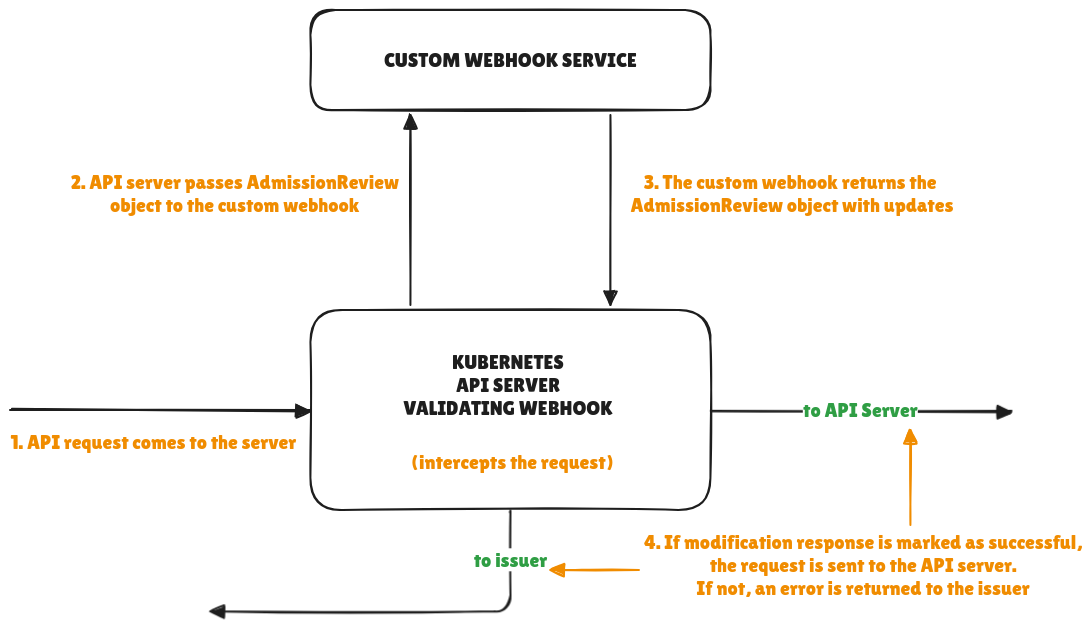

In the request flow diagram above, each Admission Controller utilizes webhooks—these webhooks are HTTP callbacks that receive and modify or validate requests that are being sent to the API server.

These webhooks are called Admission Webhooks and they are the juice of the Admission Controllers.

Admission Webhooks - the marrow in the bone

Admission Webhooks are extensions of the Admission Controllers that do the work of checking whether a request matches the required schema specified for the cluster, before being validated and stored in an etcd cluster.

There are two types of admission webhooks, each paired with the specific admission controller; they are:

- mutating admission webhooks: They contain custom code that modifies the request before it is applied to the cluster.

- validation admission webhooks: They contain custom code that validates—not modifies—a request before it is applied to a cluster.

The admission webhooks are executed in phases. The first phase sees the mutating admission webhook being executed, then the validating admission webhooks are executed in the second phase.

Note that mutating admission webhooks modifies the actual request that was issued. The issuer may not know about the changes that have been implemented. For security and transparency, the best way to utilize webhooks is to use the validating admission webhook to reject a request and have the issuer fix the request.

Creating Controllers with Custom Logic

In this section, we are going to build out a couple of custom admission webhooks for very specific examples that I have scoped out.

- the first is a mutating admission webhook that will add a custom annotation to the Pod ie

PodModified: "true" - the second is a validating webhook that will look up an annotation

teamand ensure it exists before allowing the request to pass.

This is the part where we get our hands dirty by writing some Go code that communicates using the Kubernetes-client package to the Kubernetes API server.

We will do the following in order:

- write a web server that listens for requests

- decode the request, AdmissionReview objects, that are sent by the API server

- implement the mutation logic

- implement validation logic

Let us jump right into it!

All the reference material that you will need to successfully complete the subsequent sections be found in this Github repo

1. Writing the Web Server

To write the controller, I opted to use the Gorilla Mux package. You could say this is a preference of mine. It does contain some features that I find useful.

We define our server this way:

- We define the configuration constraints that our web server should abide by:

const (

tlsDir = "/etc/webhook/certs"

tlsCertFile = "tls.crt"

tlsKeyFile = "tls.key"

webhookPort = ":8443"

readTimeout = 10 * time.Second

writeTimeout = 10 * time.Second

idleTimeout = 30 * time.Second

shutdownGrace = 5 * time.Second

)

- here, we state the directory where the server should look for its TLS configuration, the ports the web server should run on, and some timeouts for the web server.

- We add in some global variables that are needed to work with Kubernetes objects, specifically for serializing and de-serializing data.

var (

scheme = runtime.NewScheme()

codecFactory = serializer.NewCodecFactory(scheme)

deserializer = codecFactory.UniversalDeserializer()

podResource = metav1.GroupVersionResource{

Group: "",

Version: "v1",

Resource: "pods",

}

allowedContent = "application/json"

)

- the

schemehere is a registry that holds all the information about all the Kubernetes objects (Pods, Deployments, etc.) and how they are structured. - The

runtimepackage here provides the tools that will be used to work with these Kubernetes objects ar runtime. - the

codecFactoryis used to create codecs. A codec can be defined as the black box that performs the encoding/serialization and decoding/de-serialization of Kubernetes objects. - the

serializerpackage provides the tools that are needed to encode and/or decode Kubernetes objects. - for the

podResource, this is used to define the specific Kubernetes resource that we will be working with.

- We also define a

Webhookstruct that contains thehttp.Server{}andslog.Logger{}structs. This is so we can use both structs when referencing our webhook server.

type WebhookServer struct {

server *http.Server

logger *slog.Logger

}

- I have developed a liking for slog for structured logging. It feels much more intuitive to write logging statements.

- We then create our server with Mux and with the constraints we have defined.

mux := http.NewServeMux()

whs := &WebhookServer{

logger: logger,

server: &http.Server{

Addr: webhookPort,

Handler: mux,

TLSConfig: &tls.Config{

Certificates: []tls.Certificate{cert},

MinVersion: tls.VersionTLS13,

},

ReadTimeout: readTimeout,

WriteTimeout: writeTimeout,

IdleTimeout: idleTimeout,

},

}

- We register the endpoints where we will make a call to the custom webhook code to perform the admission job, either mutating or validating.

mux.HandleFunc("/mutate", whs.handleRequest(whs.serveMutatingRequest))

mux.HandleFunc("/validate", whs.handleRequest(whs.serveValidatingRequest))

mux.HandleFunc("/healthz", whs.healthCheck)

- To modularize things a bit, we create an

admissionHandlertype that takes in a request via anadmissionRequestfunction and returns a response via theadmissionResponse.

type admissionHandler func(*admissionv1.AdmissionRequest) (*admissionv1.AdmissionResponse, error)

- the

AdmissionRequestin Kubernetes is what contains all of the information about a request that is being sent to the API server—and it identifies the request as being subject to admission control. - the

AdmissionResponsecontains the response from the API server. It contains information as to whether a request has been allowed or denied. In the case of modification, it includes the new request schema to be sent to the API server.

- We then create a

handleRequestmethod that takes in theadmissionHandlerand returns ahandlerFuncto our server.

func (whs *WebhookServer) handleRequest(handler admissionHandler) http.HandlerFunc {

return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if r.Method != http.MethodPost {

whs.errorResponse(w, "Method Not Allowed", http.StatusMethodNotAllowed)

return

}

if contentType := r.Header.Get("content-type"); contentType != allowedContent {

whs.errorResponse(w, fmt.Sprintf("Unsupported Content Type: %s", contentType), http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

body, err := io.ReadAll(r.Body)

if err != nil || len(body) == 0 {

whs.errorResponse(w, "Empty or Unreadable Body", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

var admissionReview admissionv1.AdmissionReview

if _, _, err := deserializer.Decode(body, nil, &admissionReview); err != nil {

whs.errorResponse(w, "Invalid Admission Review Request", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

if admissionReview.Request == nil {

whs.errorResponse(w, "Missing Admission Request", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

response, err := handler(admissionReview.Request)

if err != nil {

whs.logger.Error("Admission review", "error", err)

response = &admissionv1.AdmissionResponse{

UID: admissionReview.Request.UID,

Allowed: false,

Result: &metav1.Status{

Message: err.Error(),

Code: http.StatusInternalServerError,

},

}

}

admissionReview.Response = response

admissionReview.Response.UID = admissionReview.Request.UID

res, err := json.Marshal(admissionReview)

if err != nil {

whs.errorResponse(w, "Error Encoding Response", http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", allowedContent)

if _, err := w.Write(res); err != nil {

whs.logger.Error("Failed to write response", "error", err)

}

}

}

In this section, we have created the web server and the logic to handle the requests that are to be sent to the API server.

2. Implementing the Mutation Logic

Here is where we handle the request that was intercepted on its way to the API server, and then change its schema—to what is prescribed, and send it on its way again.

For our specific example of using the Mutation Logic on a Pod, here is the way we define this:

- We check if the request coming in, in the

AdmissionRequestis for a Pod resource.

if req.Resource != podResource {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("unsupported Resource: %s", req.Resource)

}

- if this is not a Pod resource, then we return an error indicating that it is unsupported.

- We now attempt to deserialize (decode) the request object in the

AdmissionRequestinto a Kubernetes Pod struct.

var pod corev1.Pod

if err := json.Unmarshal(req.Object.Raw, &pod); err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to unmarshal Pod: %w", err)

}

- We initialize our patching—which is what we do to these requests as modification—struct and we apply the patches.

var patches []patchOperation

if pod.Annotations == nil {

patches = append(patches, patchOperation{

Op: "add",

Path: "/metadata/annotations",

Value: make(map[string]string),

})

}

patches = append(patches, patchOperation{

Op: "add",

Path: "/metadata/annotations/PodModified",

Value: "true",

})

- in this case, we make sure that we initialize the pod annotations and specify that a path be constructed for us.

- then, we mutate the request and by adding the actual annotation patch that we need.

- Then we marshal the new, mutated object schema and send a response back to the webhook server who will then forward the request along to the API server.

patchBytes, err := json.Marshal(patches)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to marshal patch: %w", err)

}

return &admissionv1.AdmissionResponse{

UID: req.UID,

Allowed: true,

Patch: patchBytes,

PatchType: func() *admissionv1.PatchType {

pt := admissionv1.PatchTypeJSONPatch

return &pt

}(),

}, nil

- after this response is sent back to the webhook server handler, the request ID is matched against the response ID so that the webhook server knows which of the requests it needs to work on.

A simple visual of the process flow that utilizes the MutatingAdmissionWebhook is shown here:

3. Implementing the Validation Logic

With the validating logic, the first few stages are the same as in the mutating webhook.

For our specific example, we are going to check if a particular annotation, “team”, has been added to the request that is being sent to the API server.

- We check if the request coming in, in the

AdmissionRequestis for a Pod resource.

if req.Resource != podResource {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("unsupported Resource: %s", req.Resource)

}

- if this is not a Pod resource, then we return an error indicating that it is unsupported.

- We now attempt to deserialize (decode) the request object in the

AdmissionRequestinto a Kubernetes Pod struct.

var pod corev1.Pod

if err := json.Unmarshal(req.Object.Raw, &pod); err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to unmarshal Pod: %w", err)

}

- We use the errors package to accumulate any errors that may come up during the validation checks.

var errors field.ErrorList

- the

field.ErrorListis specifically designed to collect and manage a list of validation errors in Kubernetes. - It is good practice to collect all validation errors and return them together in a response.

- For our very specific check, we perform a specific validation rule. This rule requires that every Pod must have a team annotation and that this must not be empty.

if pod.Annotations["team"] == "" {

errors = append(errors, field.Required(

field.NewPath("metadata", "annotations", "team"),

"team annotation is required",

))

}

- If any validation errors are found, it returns a response that the validation was unsuccessful, together with all the errors it accumulated. If successful, it returns a successful response.

if len(errors) > 0 {

return &admissionv1.AdmissionResponse{

UID: req.UID,

Allowed: false, // deny the request

Result: &metav1.Status{

Message: errors.ToAggregate().Error(),

Code: http.StatusForbidden,

Reason: metav1.StatusReasonInvalid,

},

}, nil

}

return &admissionv1.AdmissionResponse{

UID: req.UID,

Allowed: true,

Result: &metav1.Status{

Code: http.StatusOK,

Reason: "Validation Passed",

},

}, nil

A simple visual of the process flow that utilizes the ValidatingAdmissionWebhook is shown here:

How Does This All Tie Into Policy Enforcement in Kubernetes?

Admission controllers and admission webhooks are fundamental to policy enforcement in Kubernetes. They are the enforcement points within the Kubernetes API request lifecycle where policies can be implemented and applied.

Policy enforcement in Kubernetes is about ensuring that the cluster and its resources are managed and used according to defined rules and best practices. These policies cover various aspects, including:

- Security: ensuring that workloads and configurations adhere to security standards (e.g., preventing privileged containers, enforcing network policies, requiring security contexts).

- Resource Management: Controlling resource consumption, setting limits and quotas, and ensuring fair resource sharing (e.g., enforcing resource requests and limits).

- Operational Best Practices: Enforcing organizational standards, naming conventions, required labels/annotations, and other operational rules (e.g., mandating specific annotations for cost tracking, requiring team labels).

Admission webhooks are what are used to enforce these policies that have been laid out. In this case, they make sure the requests being sent to the API server conform to the policy that has been set—either via mutating them and/or validating them.

A great advantage of admission webhooks are that, they can be used to define custom policies that match the user’s or organization’s needs.

PS: Your favourite policy enforcer in Kubernetes, eg. GateKeeper, is an admission webhook in disguise.

We’ve tackled the complexities, and now it’s time to bring our webhook to life. We’ll deploy it to Kubernetes and then put our admission controllers and webhooks through their paces to confirm everything is configured correctly.

Setting up the Kubernetes Cluster

The highest pre-requisite for this stage is to have a Kubernetes cluster on which we can test the admission controller and the custom webhooks we have written.

The next highest pre-requisite is to ensure that the Kubernetes cluster has the necessary admission plugins. The two(2) very important ones are the MutatingAdmissionWebhook and ValidatingAdmissionWebhook.

You might be wondering how to verify whether your cluster has these admission plugins. A simple command you can use if you have access to the control plane of your cluster is this:

kubectl describe pod <NAME_OF_API_SERVER_POD> -n kube-system | grep enable-admission-plugins

- Do a quick lookup on how to find the admission plugins enabled on your cluster and how to enable them if they are not. Trust me, it is worth the time.

If you use a KinD cluster—which I use for my tests—here is a config for you with the admission plugins I use:

kind: Cluster

apiVersion: kind.x-k8s.io/v1alpha4

nodes:

- role: control-plane

kubeadmConfigPatches:

- |

kind: ClusterConfiguration

apiServer:

extraArgs:

enable-admission-plugins: LimitRanger,NamespaceExists,NamespaceLifecycle,ResourceQuota,ServiceAccount,DefaultStorageClass,MutatingAdmissionWebhook,ValidatingAdmissionWebhook,PodSecurity

- role: worker

networking:

disableDefaultCNI: true

Also, it is necessary to have the following programs locked and loaded:

yqopensslcurl

Ready to try it out? Follow the instructions in the README file of this GitHub repository to deploy and test the webhook.

NOTE: The webhooks work over HTTPS, so you need to generate secure keys and certificates for the authentication process.

Check out this link here for the walkthrough on how to create a self-signed certificate that will be used in-cluster.

BONUS!!

As a point of interest, the subsequent song was playing during the composition of the final sentence. Enjoy!!